Can We Treat Long COVID With Bacteria?

Could your gut bacteria hold the key to beating long COVID? You may be surprised by the close link between COVID-19 and your microbiome.

Summary of Key Facts

- Long COVID has no effective interventions.

- Patients with long COVID have a significantly altered oral, respiratory, and gut microbiome.

- Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in human health, and an altered microbiota is associated with many diseases and disorders.

- A treatment method to stabilize or normalize the microbiome in long-COVID patients shows promise in relieving symptoms.

In the United States alone, over 102 million people have been infected with COVID-19. The extent of their symptoms ranges from asymptomatic to severe illness that leads to death. Some may have recovered in as little as a day, but nearly 20 percent of previously or currently infected adults in the United States suffer from what is known as “long COVID.”

Long COVID, better known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, includes persistent symptoms including “brain fog,” anxiety, depression, and fatigue. The condition is thought to be linked to immune dysregulation by harmful inflammation, but the exact causes are unknown, making the prognosis and treatment similarly challenging.

However, emerging data suggest that effective long-COVID treatment may be simple. The key is having a healthy gut.

It’s long been known that gut microbiota—the collection of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses in the digestive tract—play a crucial role in human health. A stable microbiota promotes health and longevity, while an altered microbiota is the culprit of many diseases and disorders.

Therefore, the question arises: Can stabilizing the microbiota bring relief to those suffering from long COVID? To find out, let’s delve deeper into this topic.

Treat Your ‘Old Friends’ Well: One Secret to Becoming Healthier

Inside and outside the human body are trillions of microorganisms—outnumbering our cells 10 to one–bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other life forms collectively known as the microbiome.

These microorganisms and human beings are “old friends.” The symbiotic relationship between the two is essential for each one’s mutual growth and survival.

We humans, the hosts, provide the necessary nutrients, space, and conditions for microbes to survive and thrive. On the other hand, commensal or symbiotic microbiota–microorganisms that have a mutually beneficial relationship with their host–provide the host with essential vitamins, aid in the digestion of macromolecules, and serve as antagonists to pathogenic bacteria.

This interaction protects the host, facilitates the proper growth and development of the individual, and keeps both parties satisfied.

Interestingly, the gut microbiota may influence the host’s food choices to obtain what is most suitable for its proliferation, with beneficial foods arousing feelings of pleasure and unwanted foods provoking negative sensations such as nausea.

Moreover, the gut microbiota can also influence the quantity of food consumed, which leads to plausible associations with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, according to a 2018 review paper in Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. Other evidence shows that commensal microbiota is influential in socialization and reproductive behavior. Germ-free mice tend to avoid social interaction, but once their gut microbiota is repopulated to the “normal” amount via fecal microbial transplantation, they seem to engage in increased social interaction.

We often have options nowadays to choose organic food over conventionally grown food. Different types of food will relate differently to our gut microbiota. As foods treated heavily with antibiotics kill the good bacteria—our “old friends”—inside our gut, we become unhealthy.

‘Gut Feeling’ Is Not Just an Idiom but Has a Biological Basis

The complicated network known as the gut-brain axis modulates this powerful connection between microbiota and host. This axis includes the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, enteric nervous system, and central nervous system (CNS), which are critical in maintaining homeostasis and enabling optimal physiological and mental function.

There are three primary mechanisms by which sensory information is encoded in the gut: primary afferent neurons, immune cells, and enteroendocrine cells.

In short, the microbiota is the trillions of bacteria and other microorganisms that live around and inside our bodies. Most of these organisms are beneficial to us. Yet lacking a suitable microbiome is coupled with adverse effects, from gastrointestinal disorders to eating disorders and mental disorders.

A wide range of psychiatric and anxiety disorders seem to be caused or exacerbated by altered gut microbiota, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, panic attacks, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, according to the 2018 review. Even neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit disorder (ADHD), Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease may be linked to abnormal gut microbiota.

As Dr. Martin Blaser, an infectious disease expert and chair of the Human Microbiome at Rutgers University, accurately noted in his book “Missing Microbes,” “Losing your entire microbiome outright would be nearly as bad as losing your kidneys or liver.”

So how does the microbiome fare among COVID-19 patients, and are there any interventions to alleviate symptoms of long COVID by targeting the gut microbiome?COVID-19 Patients’ Altered Microbiota

There is evidence that COVID-19 patients have significantly altered oral and gut microbiota, with a weakened gut microbial network and decreased microbiome diversity. In addition, depletion of commensal bacteria has been observed at the time of hospitalization and throughout hospitalization.In a study of 106 patients with COVID-19, fecal samples were collected for up to six months after infection. The results were clear: Gut microbiota composition was significantly altered in COVID-19 patients, even in those who did not receive antibiotics.

Higher levels of Ruminococcus gnavus, Bacteroides vulgatus, and lower levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii characterized the gut microbiome of patients with long COVID.

According to the researchers, persistent respiratory symptoms were correlated with opportunistic gut pathogens, and neuropsychiatric symptoms and fatigue were associated with nosocomial gut pathogens, including Clostridium innocuum and Actinomyces naeslundii (all p<0.05). Butyrate-producing bacteria, including Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, showed the most significant inverse correlations with long COVID at six months.

Moreover, the analysis revealed elevated levels of opportunistic and nosocomial gut pathogens, particularly strains in the Streptococcus bacterial family, which are microorganisms that can cause infections when the host’s immune system is compromised or when acquired in health care settings such as hospitals. These pathogens are associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms and fatigue, which coincide with long-COVID symptoms.

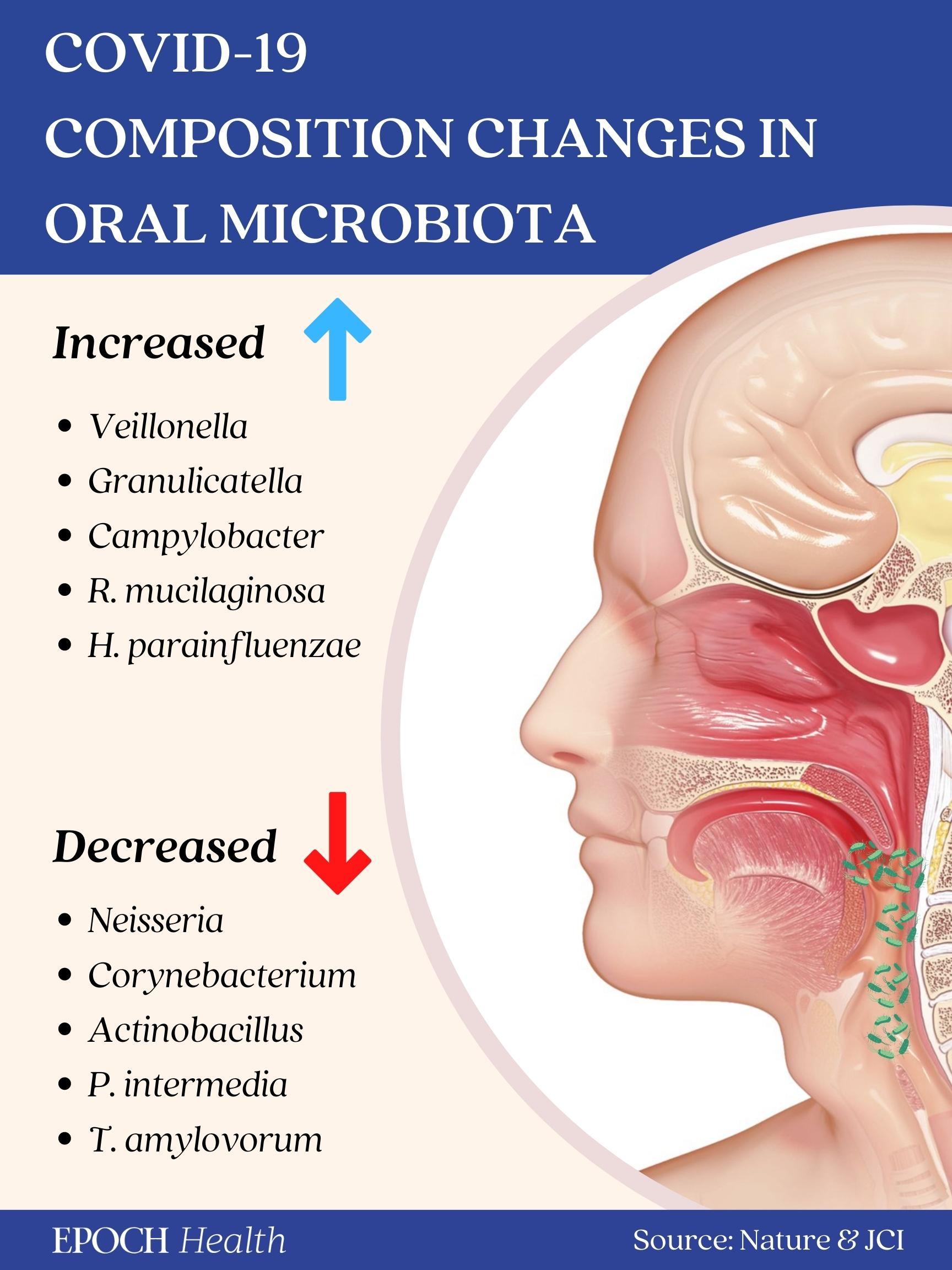

Yet it wasn’t just the gut microbiota that was altered. In other studies (1, 2), when the oral microbiota composition was examined, researchers observed that patients with prolonged symptoms of COVID-19 had significantly higher numbers of bacteria that induce inflammation. Interestingly, the oral microbiome of patients with long COVID was similar to that of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

And, as expected, the microbiota composition in the respiratory tracts was also altered in COVID-19 patients. When upper and lower respiratory tract samples were collected and sequenced, researchers found a higher abundance of bacteria, such as Peptoniphilus lacrimalis and Campylobacter hominis, as well as a decrease in commensal bacteria.

These findings suggest a correlation between long COVID and the oral, respiratory, and gut microbiome, hinting at the possibility that dysfunction or abnormality in the microbiome network may have contributed to the disease.

The correlation between an altered gut microbiome and COVID-19 is so strong that diagnostic methods have been proposed, which include sampling patients’ fecal microbiota and rendering a diagnostic according to the composition and abundance of the microbiota present.

The good news is that there may be strategies to stabilize and recover healthy intestinal microbiota to reduce disease severity.

Use Good Bacteria to Treat COVID-19

Given the large number of people affected by COVID-19, there should be compelling reasons to explore microbiota modulation to promote prompt recovery and lessen the impact of long COVID-19 syndrome.

The first of these interventions is the administration of probiotics and prebiotics. According to a review article in Frontiers in Microbiology, probiotics are nonpathogenic microorganisms that, when taken in suitable amounts, can enhance the host’s microbiome equilibrium and positively affect host health.

On the other hand, “prebiotics are substances that cannot be digested by the host but can be selectively utilized by host microorganisms” to produce compounds that promote the host’s health.

Probiotics and prebiotics are essential in the interactions between the host and microbiota, resisting pathogens, regulating immunity, and influencing metabolism.

As mentioned above, the microbiota in COVID-19 patients has undergone significant changes, most of which have unfavorable health effects on the body. Therefore, if probiotics and prebiotics are administered effectively, they can ameliorate these patients’ symptoms.

For example, in a clinical trial, oral probiotics primarily composed of bacteria in the Lactobacillus family were administered and in as little as 72 hours, nearly all patients treated with bacteriotherapy showed remission of diarrhea and other symptoms compared to less than half of the group without supplementation. The estimated risk of developing respiratory failure was eight-fold lower in patients receiving oral bacteriotherapy.

However, the number of patients in this study was still low, and the results were preliminary. More studies should be conducted to further address the role of bacteriotherapy in COVID-19.

Nonetheless, a bibliometric analysis revealed that probiotic or prebiotic interventions could indeed boost resistance to COVID-19 infection, lessen the disease’s duration and symptoms, and positively impact the host’s immune system.

Although the correlations mentioned above provide some support for gut microbiota’s significant role in COVID-19 infection and prognosis, the relationship between microbial changes and COVID-19 does not prove causation. This distinction is crucial before considering the use of microbiota-based therapy for COVID-19.

However, as probiotics and prebiotics are readily accessible–in foods such as yogurt, kefir, kimchi, and kombucha–there is no reason not to give it a chance; it may just prove beneficial.

Of course, the type of food consumed and its composition affect the structure and health of the gut microbiota. Healthy diets such as the Mediterranean diet, which is rich in fiber, unsaturated fatty acids, low in food additives, and low in carbohydrates, benefit the diversity and stability of the microbiota, leading to overall health and well-being.

Other Treatments May Also Regulate Microbiota

Antibiotics have been the primary means to treat infectious diseases. However, as outlined above, simple diet changes and supplementing with probiotics and prebiotics can provide relief and aid recovery.

Are there any other alternative treatments that can be implemented to help people recover from long COVID?

The first alternative that shows a strong promise is traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). TCM can have a direct positive effect on regulating the intestinal mucosal barrier, aiding in the composition of the gut microbiota.

Additionally, ingredients found in TCM, such as saponins and polysaccharides, are beneficial metabolites, improving gut microbiota stability and leading to general wellness.

One study showed that, alongside physical and mental health, meditation practice may positively impact the gut microbiota, as well. Meditation cohorts experienced enriched gut microbiomes with increased beneficial bacterium species compared to control groups.

A healthy microbiome is associated with reduced anxiety, depression, and overall enhanced immune function, all of which may be helpful in cases of long COVID.

If you or a loved one has been affected, the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Working Group's (FLCCC) I-RECOVER protocol can give you step-by-step instructions on how to treat reactions from COVID-19 injections.

.png)

.png)

.png)

Comments